Virginia prison communication policy doesn’t need to be ‘explicitly stated’

Families of incarcerated people, advocates and media encounter roadblocks to accessing information.

Warning: This story discusses self-harm.

Tomeka Wallace didn’t know her son was being transferred from Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison until she got a call in February from a Maine prison official.

Demetrius, her son, was among a group of men at Red Onion who previously harmed themselves and participated in a hunger strike to protest conditions at the super-maximum security facility in the southwest portion of the state.

“I just happened to get a call that I almost didn't answer,” Wallace recalled. “The lady said, ‘Do you know Demetrius Wallace? … Well, your son is in Maine.’ I said, ‘In Maine? You mean the state?’”

Wallace is hundreds of miles from where her son’s now being held and said the entire carceral system needs to be changed. But she’s grateful for activist groups working throughout the commonwealth, which share information with incarcerated people and raise public awareness of what’s transpired at the facility.

Those groups have claimed that the department’s head spokesperson, Kyle Gibson, is “attempting to block media access to adults in custody.”

Since the nine confirmed incidents of self-harm began last year, local, state and international media — including The New York Times and The Guardian — have covered the story. The self-inflicted burns and attendant media attention have coincided with what men incarcerated by the Virginia Department of Corrections and prison abolitionists see as a coordinated effort to impede communications.

Gibson emphatically denied the complaint via email: “This claim is completely false.”

But in email exchanges with media, he’s referenced unwritten rules when declining to answer questions, saying that communications staff don’t generally respond to inquiries without proof of a publication home. That kind of opacity has raised alarm among press freedom advocates who see a broader trend of government agencies withholding information that should be available to the public.

I sent a series of questions to Gibson on May 1 for a story I told him likely would be for the local public media outlet WVTF/Radio IQ. After receiving a reply saying the request was being processed, no additional information was sent. I followed up on May 7, adding a question about transfers at the facility.

A week later, Gibson wrote, “The VADOC will reconsider this request if you are able to provide a confirmed outlet for your reporting.”

That policy doesn’t exist in Virginia Department of Corrections records, according to a Freedom of Information Act request. Gibson later explained why: “This response is VADOC common practice and is not explicitly stated in policy, nor does it need to be.”

A version of the story was later published by WVTF/Radio IQ and also shared through Red Onion Resources, a newsletter unaffiliated with a traditional media outlet.

Virginia Del. Mike Jones, who visited Red Onion following the reports of self-harm, has been vocal about a range of issues he believes need to be addressed at the facility. That includes the racial dynamics between prison staff and the people incarcerated there, the economics of the carceral system — and how information is accessed.

“It's not in their best interest to be forthcoming. That's why we have Freedom of Information Act [requests],” Jones said this spring. “We wouldn't need these laws if people shared it freely, but they don't. I understand why they don't.”

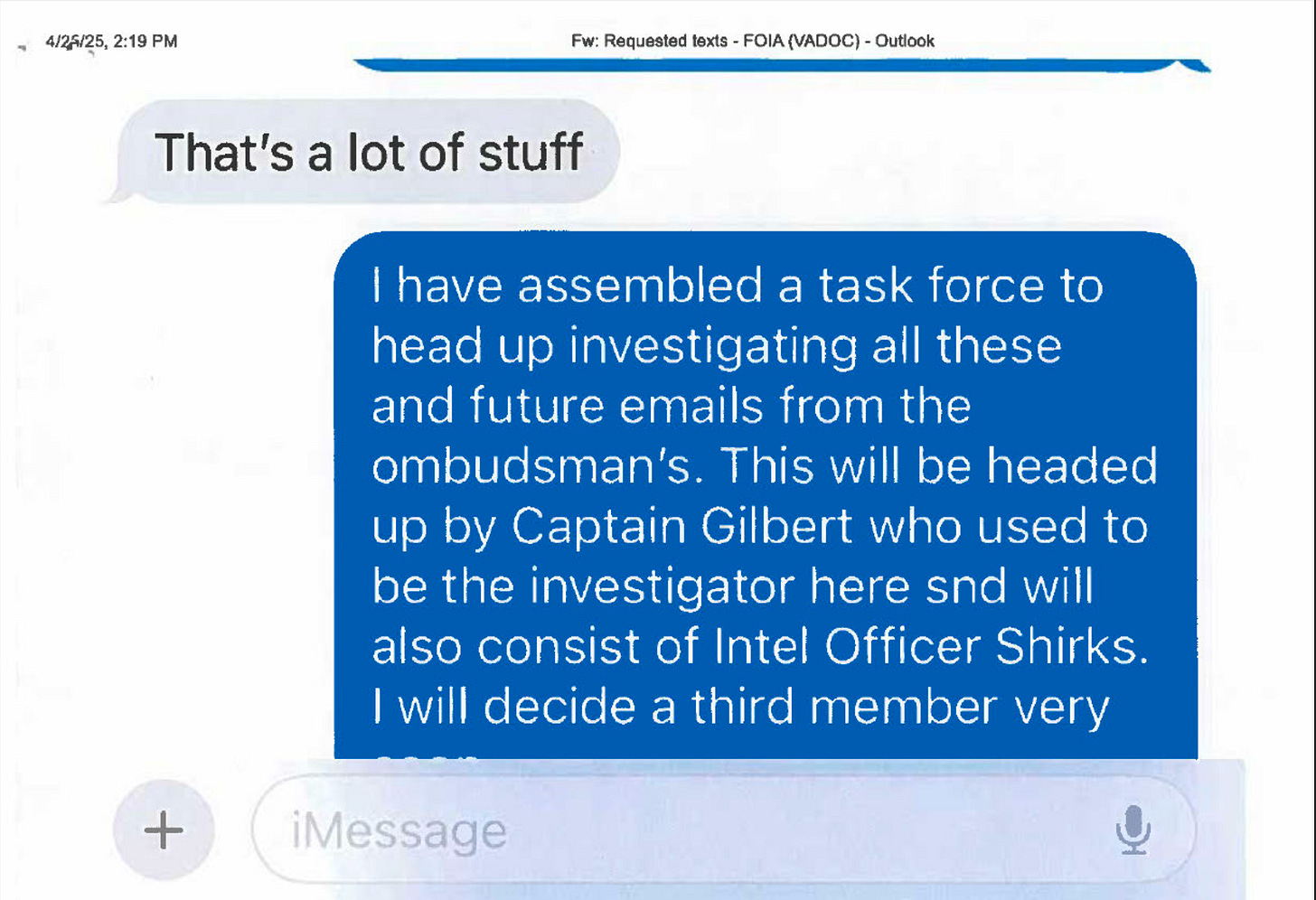

Included in a batch of FOIA documents I received was a text exchange that discussed selecting three Department of Corrections staffers to look into dozens of grievances incarcerated people at Red Onion have filed since the beginning of the year. Two people were identified in the exchange and another was to be selected later.

So, I sent Gibson a note to find out more.

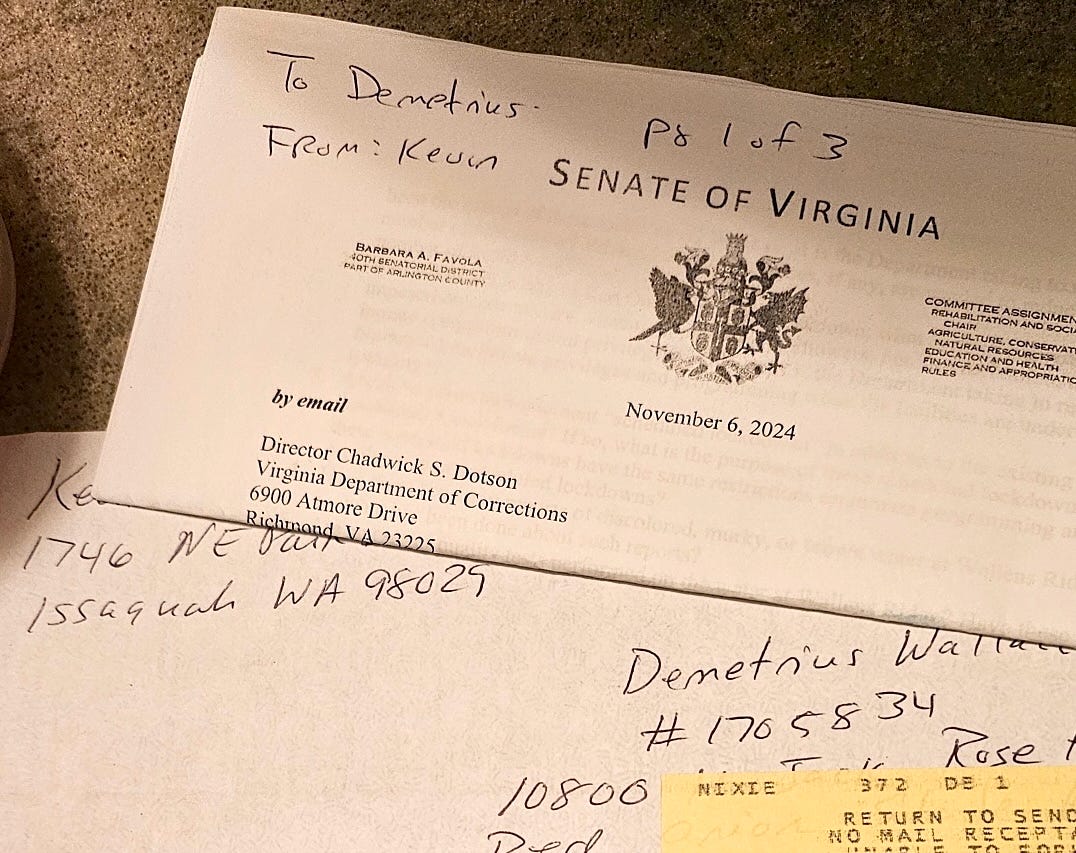

He wrote that these were not formal positions and that staffers were selected “on a case-by-case basis.” But because the possibility of adding another person to that ad-hoc group was mentioned, I also emailed Robinette Perry, who in documents was identified as the department’s ombudsman services manager. I didn’t receive a response.

Gibson later followed up with an email: “Unauthorized Media Contact.” His note detailed the email to Perry, a description of the department’s media policy for staff and a request: “Please provide acknowledgement of this email, along with the email address of your editor.”

Neil Brown, president of The Poynter Institute, described barriers to accessing government information in the organization’s 2024 report, Shut Out: Strategies for good journalism when sources dismiss the press: “Not all, but many who do the public’s business have taken a misguided and unfortunate stance that they are under no obligation to make themselves or their work available for independent journalistic review, even though it is an essential component of our civic life.”

Austin Arocho was initially incarcerated at Red Onion, though he’s since been moved to Virginia’s Wallens Ridge State Prison, his mother, April Wright, said. She said he was among the men who purposely injured themselves in 2024.

Wright said she hasn’t spoken with him since January.

“I've been sending him emails — like three or four emails every week. I've not gotten any responses back from that,” Wright said. “They took his phone privileges — he's supposed to get them back at the end of July. But every single time they do that, it's always something else comes up and they take it away from him again.”

Department policy indicates it can restrict or limit communications of the people in its custody “to protect public safety or facility order and security.”

Apart from the emotional toll, not being able to talk to Arocho has impeded Wright’s ability to act as his legal advocate.

In November 2024, Wright said a Department of Corrections official called her after Arocho was found hanging from a sheet slung over the door to his cell. She said the official told her that Arocho had flatlined, but was later resuscitated at an outside facility. She’s still working to gain access to medical records from the incident.

“For any mother that's out here who's never dealt with this stuff before — it's like they feel helpless and hopeless, and they don't know what to do — they don't know where to turn,” Wright said. “It eats at you so bad, it ends up giving the people out here health conditions.”

Stephanie Krent, a staff attorney at the Knight First Amendment Institute, identified a broad trend of deteriorating trust between the public and government agencies.

“All of us, as members of the public, have an interest and perhaps an obligation to understand what's going on in jails and prisons across the country,” she said, speaking generally. “To cut off one of the most important avenues for communicating that information, which is the impacted people themselves, that's incredibly problematic.”

She also said that in some cases, prison staff are given significant leeway to determine what kinds of correspondence are allowed to enter and leave prison facilities.

“I think when you see that sort of fray, then you can see further entrenchment,” she said, speaking broadly about how information is shared among prison staff, incarcerated people and their families. “What you really want, if you want to run a DOC that is successfully rehabilitating people into the community, is much more close connections and much more information going to families of people that are incarcerated, making sure that everyone feels kind of involved in decision-making and understands what policies are actually in place.”

On a mid-June afternoon, Tomeka Wallace finished working the line at Happy Café, her Virginia Beach restaurant, and gave me a call. She said her son’s doing better in Maine — both mentally and physically — than when he was at Red Onion. The transfer out of the Virginia Department of Corrections also made it easier for her to communicate with Demetrius.

“Prior to this, it was hell on wheels,” Wallace said about her emotional state before the transfer. “I'm a little bit better about it now because I know where he is — I speak to him on the regular. He has access to send me email, he has access to give me a call. I'm thankful, in my situation, for what has taken place.”

This story was published in collaboration with Poynter.

From around the internet

Stories you might have missed

State probes death of an inmate at Wallens Ridge (WVTF)

Aubrey McKay, who was set to be released in July, died while in state custody last month, according to WVTF/Radio IQ.

Stacy Carter, McKay’s mother, recounted a discussion with the medical examiner: “She told me all the head trauma he had, the black eyes he had, and that he had bruises on his arms and ankles from the handcuffs and the shackles. But her biggest concern was the fractured Adam’s apple, and she wasn’t happy about that, so she opened up an investigation.”

Extensive lockdowns at Red Onion State Prison leave loved ones in the dark for weeks at a time (WRIC)

In June, Red Onion had been on lockdown for 46 days — or about one-third of the year to that point.

VADOC told the TV outlet that mail service is not interrupted by lockdown, though a woman named Meg, whose partner is incarcerated said: “I think the biggest thing is really, honestly not knowing if they’re even alive. So, when people are like, ‘They did the crime, they need to do the time,’ that’s fine. But there’s treatment that’s going on that is just unnecessary.”

The woman said she’s had multiple pieces of mail returned to her.

When fire is the only way out (Inquest)

This is from earlier in the year, but works to depict the experiences people had at Red Onion that led them to self-harm. It’s written by Jenifer Black and Noel Harahan; the latter runs Prison Radio.

“In their intense pain, through emergency surgeries and skin grafts, these men have finally been seen and heard by the outside world, by outside doctors, by us, and by Prison Radio listeners,” the duo wrote.

An aside — pertinent to the reporting above — comes about halfway through the piece: “Inquest sent the Virginia Department of Corrections a detailed request for comment in connection to the various reports and allegations in this article. A spokesperson responded but didn’t address or deny any of them, noting that the department ‘does not typically respond to groups writing from an advocacy-based mission with the appearance of operating as a journalistic news outlet.’”